Industry Insights

Thank you for your patronage, Mr. Kauffman

The world of business doesn’t use the word patronage so much anymore. We’re more apt to hear, “Thank you for your business” or even less gratefully, “Your transaction is complete.” In the world of consumerism the customer is king, lowest price wins and doing business is nothing more than money changing hands.

Patrons, however, recognize a different world. Though often the captains of industry, they also understand the cry of the artist. A cry that begs the world to travel down a new road. Patrons are willing to be led. They understand the great potential for our world and so they free artists to take risks, explore creative limits, and push themselves to do their very best. The Patron of course also enjoys the exclusive and rare goods that can result. The artist enjoys the challenge and recognition of his work.

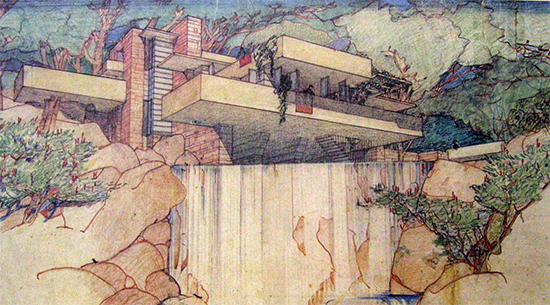

This past week my wife and I had the privilege of visiting Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater at Bear Run deep in the Laurel Highlands of Southwestern Pennsylvania. Fallingwater is considered by many to be Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatest masterpiece. The experience of seeing the iconic house so thoughtfully positioned in its rugged and wooded surroundings was spectacular! I left inspired.

photo by Jason Bouwman

It’s called Wright’s Fallingwater and rightly so. And yet as we explored this architectural wonder I felt an immense sense of gratitude to Mr. and Mrs. Kauffman too for commissioning the work, for allowing it to happen. Wright brought his ideas, his passion, his art to Bear Run. But it was the Kauffmans who had the power to make it happen. They paid dearly for this house and then shared it generously. After the Kauffmans passed away the whole estate was donated to the public to enjoy what they had made.

Fallingwater is probably the best expression of Wright’s design principle of organic architecture, or architecture that respects and integrates fully with the landscape in which it’s placed. The topography of the ravine with its horizontal layers of sandstone is instantly recognized in the lines and scale of Fallingwater’s cantilevered terraces. The terraces, or “trays” as they are called, seem to cascade down the steep incline – a major design theme for the home that Wright exploited to great effect. Stone quarried from the site blends the building to its natural setting in the most immediate and genuine way.

photo by Jason Bouwman

If Fallingwater is inspiring to look at from the outside then it is even more so to experience its interior spaces. Organic architecture, a term that Wright coined, describes not only the relationship of the building to its natural surroundings but also the thoughtful design of the interior space and the experience created for its inhabitants. Wright designed from the inside out.

Large open areas are accessed through narrow, low passages giving one the feeling of being compressed and then released. In this way Wright encourages movement through the hallways and simultaneously makes the living spaces feel much more open and spacious than they actually are. Every room is meant to have an ample view of the outdoors. While Wright designed from the inside out, he effectively brought the outside in. This is my favourite aspect of his design. The interior is illuminated during the day by natural light pouring in through horizontal expanses of glass. When the windows are opened the rooms are filled with the cool air and sound of the gurgling and splashing of the waterfall.

Visitors move freely along the natural flagstone floor from exterior to interior and back out to exterior again without passing over a threshold. Fallingwater is more than 5,000 square feet but an incredible 45% of that space moves out of doors and onto terraces. But the most dramatic example of bringing the outside in occurs in the core of the home where the main boulder on which the house was built rises up through the floor to form the hearth. It’s genius!

Wright was a passionate artist. He was intentional about every detail in his designs and fought tenaciously to ensure his vision was realized and that his art was not compromised. This wasn’t always fully appreciated by his clients. Stories of his “battles” with clients abound. In one, when a client asked for more closet space, Wright refused saying it wasn’t right for the client to have so many pairs of shoes. He also refused to include attics, garages, or basements. When Mr. Kauffman questioned the integrity of several beams that Wright had designed, Wright fumed and threatened to cancel the entire job.

There are times when Wright appears petulant and snobbish but I’m convinced that we owe as much to his personality as we do to his creative genius that we have a place like Fallingwater to inspire us today.

And of course we owe a great deal to the patrons, Mr. and Mrs. Kauffman, for recognizing Wright’s genius, for trusting him and for allowing him to lead them well outside of their comfort zone. When the Kauffmans commissioned Wright to design what would become Fallingwater, they brought him to their favourite spot on the property – the waterfall. They fully expected Wright to position their new home downstream with a beautiful view of the dramatic cascade. So you can imagine their surprise when Wright showed them the first concept drawing depicting an extraordinary structure perched right atop and in the waterfall itself. The Kauffmans, too, must’ve possessed the gift of vision. This was the 1930s and Fallingwater is considered a contemporary piece by today’s standards.

At the time of Fallingwater’s design, a decent home in nearby Pittsburgh cost about $5,000. The Kauffmans, owners of a high-end department store bearing their name, were people of means. They budgeted $20,000–30,000 for their project. By the time construction was finished on the main home and adjoining guesthouse, the bill had reached $155,000. And yet there is no mention that this was a major point of contention for the Kauffmans. On the contrary, it is reported that Mr. Kauffman and Mr. Wright remained friends and in the years that followed the completion of Fallingwater, Kauffman commissioned Wright for additional projects.

I believe Kauffman knew a good thing when he saw it. He wasn’t tricked into building Wright’s design. He was captured by it. He was an equal collaborator on Fallingwater and needs to be recognized for his own vision and his patronage. The work that Wright and Kauffman built together attracts between 130,000 and 160,000 visitors to the Bear Run property each year. Last year (2013), Fallingwater welcomed its five millionth visitor. That’s right. Over five million people have come to see their vision in real life. I’m thrilled to be counted among them.

photo by Jason Bouwman

The idea of patrons and artists seems confined to the world of the wealthy and the high arts. But we’re all patrons of sorts. Our entire lives, including the purchases we make and the businesses we patronize, tell a story. James K.A. Smith, editor of Comment magazine, recently wrote that “when we spend our money, we we are not just consuming commercial goods, we are also fostering and perpetuating ways of being human. To be a patron is to be a selector, an evaluator, and a progenitor of certain forms of cultural life. You didn’t realize that you exercised such power did you?”

Few will have the power that Kauffman did to create magnificent art. But we can all be thoughtful and a maybe a little more courageous in how and with whom we spend our money. We won’t all have clients like the Kauffmans but we can be more intentional in encouraging our clients to let us do our very best and rewarding them with something meaningful – and perhaps even inspirational – when they do.

Written by Jason Bouwman, RGD

October 9, 2014