Industry Insights

En plein air

There are a few rare moments in life, that have the ability to change the trajectory of a person’s future. Rarer still are those powerful enough to set someone on a completely different path. For some, that path may bring them into classrooms, offices, or studios, but for those lucky enough, that path leads outdoors.

These moments might be traumatic, they could be an inspiring encounter with a stranger, or even an inspiring story. My moment was a curiosity piqued while standing in line at an art supply store.

I entered the world of commercial art as a freelance illustrator. During this time I created various works for local clients from my studio which was located in the basement of our 70’s era back-split on Palmer Dr., in Burlington. I spent hours hunched over the wooden drawing table that my father had made for me. I was intensely focused and the hours flew by; nevertheless there were times when I needed to get out. Frequently I found respite from my relentless schedule and pressing deadlines at the art supply store. It was during one such escape that my path was altered.

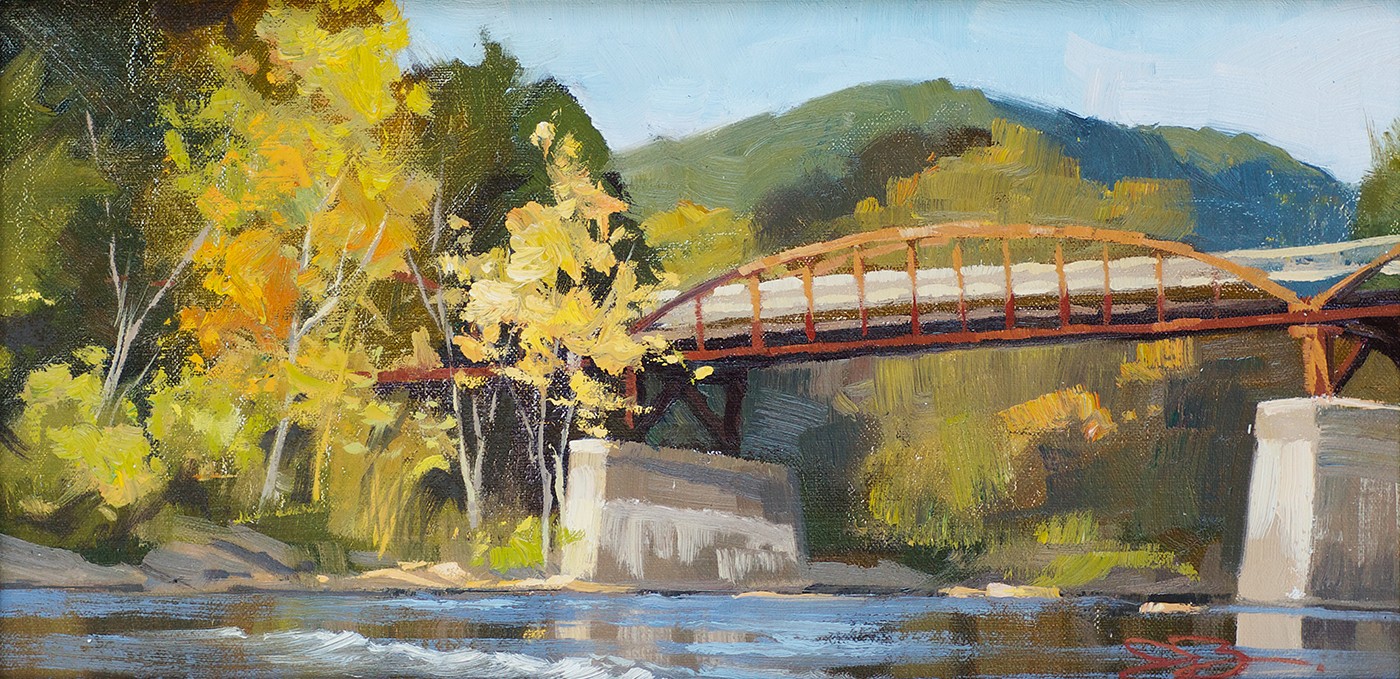

While on one of my supply trips to Curry’s Art Supplies in Hamilton (the store is still there actually and it’s still a delight to “escape” to every now and then) I first discovered something called “Plein Air Painting”. Normally I would flip through a magazine - either South-western Art, American Artist, or American Art Review – as I stood at the checkout line. I admired the images arranged on the pages, images created by artists much further along in their careers than I. Specifically, I admired a certain type of image; landscapes that had a certain quality to them. They were often freely painted and yet carefully composed. They were both beautiful and held some deeper truth. Curious, I noted that the captions under the pictures described the paintings as “Plein air”. I had no clue what it meant, and I remained ignorant for some time. What I did know was that if a painting was even remotely described as plein air, I liked it.

Not having access to Google, it took me a while to determine that plein air referred to paintings created outdoors from observation. To my surprise this was nothing new. “Plein air painting,” literally translated from French as “open air painting”, has been the practice of fine artists going back centuries. But it was the Impressionists and Barbizon painters of the mid 19th century who really elevated this practice and made it popular. In their efforts to capture natural light and atmosphere, these artists took their tools and materials outdoors, drawing inspiration from and responding to nature directly. If you like Monet, Renoir, Polenov or even Canada's own Group of Seven, chances are that you find en plein air works as captivating as I do.

“There is something invaluable in being outdoors – not only for art but for the body and soul that produces that art.”

Jason Bouwman

Development of the portable French box easels combined with the advent of tubes of coloured paint made painting outdoors easier and caused the popularity of outdoor painting to surge in the 1870s. This popularity has endured throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century despite the many challenges associated with it.

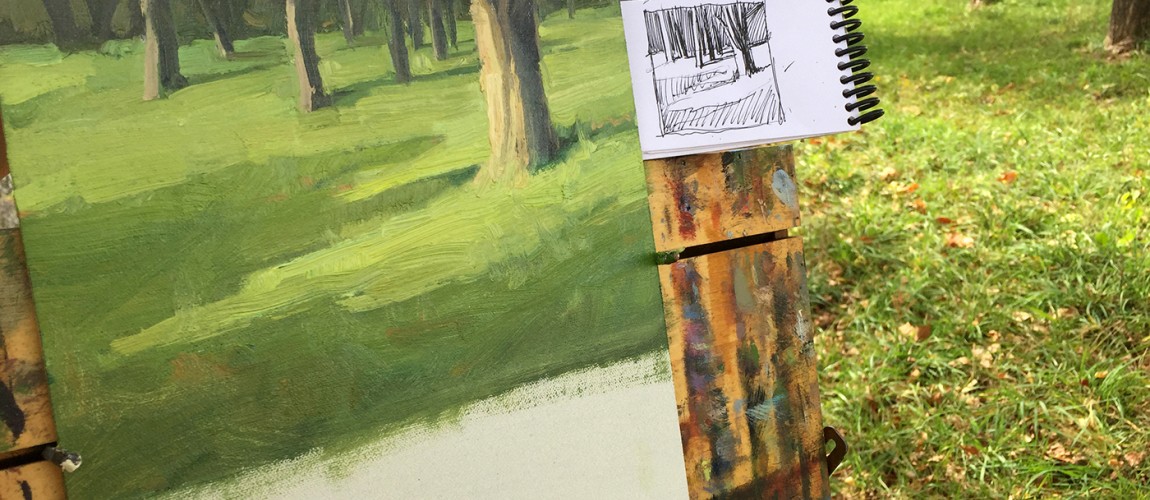

Not long after discovering what plein air painting was all about, I was inspired to try it myself. I threw a canvas board and some art supplies in a grocery bag, hopped in my truck, and drove north of town to find a suitable location. For me, the Niagara Escarpment in North Burlington has always been inspirational so it is no wonder that I parked on the shoulder of Britannia Road just outside of Lowville, ON to try my hand at plein air painting; that was September 1999.

I still remember the exhilarating feeling I had sitting on the tailgate of my truck, inhaling the fresh country air as I tentatively laid my first brushstrokes; the sound of birds and rustling leaves made more evident by the lack of phone or email notifications. I’ve heard hunters describe early mornings spent in their tree stands with similar elation. When we stop to enjoy sustained, quiet, thoughtful observation of natural beauty - when we’re immersed in it - we become aware that the world around us is teeming with life. Insects buzz and crawl (sometimes into my paint), birds chirp, squirrels scurry. A local resident walking his dog strolls by pausing just long enough to satisfy his curiosity and exchange pleasantries. In painting en plein air I become a curiosity, a reason for others to pause.

Painting outside is challenging due to constantly changing light and atmospheric environmental conditions. Naturally, this necessitates speed and concrete decision making. It means concentrating on capturing the essence of a scene and not all of its details. Monet demonstrated this realignment of focus in his famous “Haystacks” paintings which show the essence of a scene transforming over time. Because of the changing conditions most outdoor painting sessions don’t last longer than a couple hours. And while this is not much time to complete a painting, in today's sped up, easily distracted world of digital communications, it feels like an eternity to remain in one place carefully observing and analyzing. Maybe it is for that reason that this ancient practice has become so relevant today. Instead of clicking a button and moving on, painting requires prolonged immersion in the subject matter, it requires the painter to be present and there is something really good about that. Painting increases both our attention span and our appreciation of the beauty that surrounds us.

When painting outdoors you face a variety of conditions. Beating sun. Wind. Rain. Bugs. This is far removed from the climate controlled environs of the office/studio and it is humbling; it evokes ones emotions and these emotions find their way into the painting itself. Other times the challenges can prove to be too much. With flies in the paint, wind blowing an easel into the dirt, or rain washing the paint away there is a reason that artists who spend much of their time outdoors are affectionately called “Com-plein air painters.” Prepare as we might, being outdoors always provides us with opportunities to be humbled. There is something really good about that too; it produces character and resilience.

If I’m to be honest my actual painting efforts didn’t amount to much at first. I was however, successful enough that I was encouraged to try again. I quickly decided to make this a regular habit. So each Friday for many years I would stop working in the studio at 2:00pm to head outside to paint en plein air. I spent a lot of time driving around North Burlington in my 1981 Chevrolet pickup finding and painting whatever inspired me in the moment. As you might expect I produced many paintings during these precious moments, but less expected was how much getting to know the local landscape in more detail meant to me. It was glorious. I also believe it was healthy.

You see, there is something invaluable in being outdoors – not only for art but for the body and soul that produces that art. Don't take my word for it. Many studies support the idea that being outdoors benefits a persons mind, body, and spirit. Researchers are rediscovering the importance of making sure that children spend non-programmed time exploring nature. They have found that time spent outdoors can be critical to the development of children’s motor skills and cognitive functions. For adults being outdoors offers a simple antidote to today's fast-paced, sedentary lifestyle. We spend a lot of time indoors, especially at work and it concerns my colleagues and I. It bothers us enough that we're thinking about how we can spend more time outdoors.

For me, it's easy. I will paint, en plein air. If you see me around, give me a wave. As it is, I will always be grateful for the moments spent standing in line at the art store where I learned about the path to better art and that it led me outdoors.

You can see more of Jason's paintings at jasonbouwman.com

Written by Jason Bouwman, RGD

July 12, 2017